Getty images

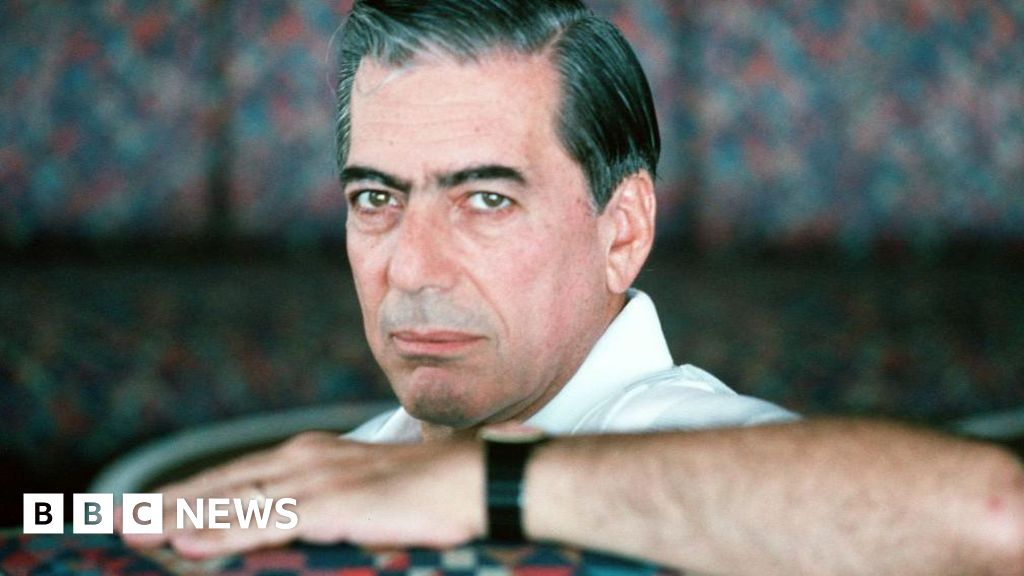

Getty imagesMario Vargas Llosa, who died at the age of 89 in her Natal Peru, was an imposing figure in the literature and culture of Latin America which rarely moved from controversy.

With more than 50 works in his name, many of which were largely translated, Vargas Llosa won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010 when the judges nicknamed a “divinely gifted storyteller”. His representations of authoritarianism, violence and machismo, using a language and rich images, made him a star of the literary movement of the Latin American arrow who shone a world projector on the continent.

First of all, sympathetic to left-wing ideas, he developed with the revolutionary causes of Latin America, ultimately in the event of the Peruvian presidency with a center-right party in 1990.

Vargas Llosa was born in 1936 from a middle -class family in Arequipa in southern Peru. After his parents separated when he was a child, he moved to Cochabamba in Bolivia with his great-grandparents. He returned to Peru at 10 and six years later, he wrote his first play, The Escape of the Inca. He graduated from the University of Lima, studied in Spain and then moved to Paris.

His first novel, The Time of the Hero, was an indictment of corruption and abuse in a Peruvian military school. Written in a time when the country’s army exercised an important political and social power, it was published in 1962.

His energetic and threatening imagery was condemned by several Peruvian generals. One accused Vargas llosa of having a “degenerate spirit”.

He was based on the writer’s time in adolescence at Leoncio Prado Military Academy, which he described in 1990 as “an extremely traumatic experience”. His two years there made him see his country “as a violent society, filled with bitterness, made up of social, cultural and racial factions in complete opposition”. The school itself burned 1,000 copies of the novel on its field, said Vargas Llosa.

His second experimental novel The Green House (1966) took place in the Peruvian desert and jungle, and described an alliance of pimps, missionaries and soldiers based on a brothel.

The two novels helped to found the literary movement of Latin American boom from the 1960s and 1970s. The boom was characterized by experimental and explicitly political works which reflected a continent in disorders.

Getty images

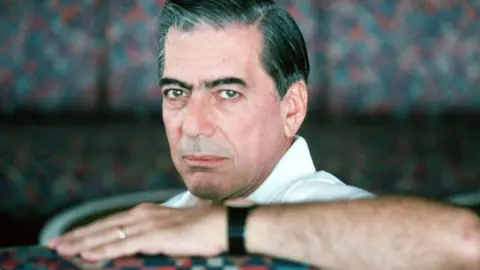

Getty imagesHis main authors, who included the Colombian friend of Vargas Llosa and sometimes Rival Gabriel García Márquez – who was the pioneer of the writing style of Kaleidoscopic magic realism – has become household names and their works were read in the world.

Famous, the two authors did not speak for decades after Vargas Llosa struck García Márquez in the face in a Mexican cinema in 1976. According to the reasons why Vargas Llosa struck his Colombian friend differs.

The friends of García Márquez declared that the dispute had revolved around the friendship of García Márquez with the then woman of Vargas Llosa, Patricia, but Vargas Llosa told students in a University of Madrid in 2017 that she had been in their opposite opinions on Cuba and her communist leader, Fidel Castro.

They reconciled in 2007 and three years later, in 2010, Vargas Llosa received the Nobel Prize – the first South American writer to be chosen for the Prix de la Littéture since Gabriel García Márquez took the honor in 1982.

A large part of the work of Vargas Llosa is inseparable from instability and violence in certain parts of Latin America in the second half of the 20th century while the region experienced waves of revolutions and military regime.

His new conversations in the cathedral (1969) were celebrated to expose how the Peruvian dictatorship of 1948-1956 under Manuel Odría controlled and finally ruined the lives of ordinary people.

Like many intellectuals, Vargas Llosa supported Fidel Castro, but was disillusioned by the communist leader following the “Padilla” affair when the poet Heberto Padilla was imprisoned for criticizing the Cuban government in 1971.

In 1983, Vargas Llosa was appointed president of a commission investigating the horrible murder in a village in the Peruvian Andes of eight journalists, who became known as the Uchuraccay massacre.

Peruvian officials argued that journalists had been killed by indigenous villagers who had confused journalists with members of the Maoist Guerrillas group Shining Path.

The Commission’s report supported the official line, leading to fierce criticism of Vargas Llosa by those who thought that the horrible nature of the crime and the horrible mutilations inflicted on the body were the mark of an infamous anti-terrorist policeman rather than signs of “native violence”.

Moving further on the right on the political spectrum, in 1990, Vargas Llosa ran for the Peruvian presidency with the coalition of the Frente Democrático of the center-right on a neoliberal platform. He lost against Alberto Fujimori, who then ruled Peru for the next 10 years.

Despite the criticisms of him about the investigation into the Uchuraccay massacre, Vargas Llosa continued to expose the terror of the state and the abuse of power through literature.

His novel The Feast of the Goat, published in 2000, focused on the dictator Rafael Trujillo, who ruled the Dominican Republic for 31 years until his assassination in 1961. The novel praised the Nobel Prize Committee for its “structures of power” and “images of the resistance, revolt and defeat of the individual”.

Other works have been adapted for the big screen. His book Aunt Julia and the screenwriter, based on his first marriage, were adapted in 1990 in a Hollywood feature film, Tune in Tomorrow.

His subsequent work has covered figures as diverse as the Irish nationalist Roger Casement (The Dream of the Celt, 2012).

He spent the last years of his life in Peru and Madrid.

Getty images

Getty imagesThe author appeared in the pages of Spanish Gossip Hola magazine after leaving his 50-year-old wife in 2015 to be with the Spanish-Filino-Filipino Isabel Presys, the mother of the popular Latin singer Enrique Iglesias.

He also continued to attract criticism for controversial remarks.

In 2019, he was convicted of having blamed the rise of journalists’ killings in Mexico – more than 100 in the last decade – on the expansion of press freedom “which allows journalists to say things that were not authorized before”. Although he also said that “drug trafficking plays an absolutely central role in all of this”, some commentators said that he had failed to express his sympathy with the victims and their families.

And in 2018, he caused a sensation when, in a chronicle for the Spanish newspaper El País, he called feminism “the most determined enemy of literature, trying to decontaminate it from machismo, multiple prejudices and immoralities”.

He died in Lima on April 13 surrounded by his family and “in peace”, announced his son Álvaro Vargas Llosa.

With his death, the last of the big stars of the Latin American arrow disappeared.